The Covid19 Pandemic came as a huge shock to the world.

You may still recall the eerie sense of unease and uncertainty that gripped us in early Spring 2020, particularly in those first weeks and months faced with a little understood virus, panic buying in supermarkets, and lockdowns.

At the time, it was very difficult to predict, how and when the pandemic would end, or what the post-pandemic world would look like. Did anyone imagine that we would simply return to the pre-pandemic normalcies once a vaccine was developed? I don’t think so.

But neither did anyone predict the global supply chain forces that have defined the period both during and post-pandemic – exacerbated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Could the decade have started on a less positive note?

At least the worst of the pandemic is now behind us, but we are still coping with the socio-economic aftermath and continued supply issues, from basic convenience goods to industrial raw materials.

Unforeseen consequences

Modern supply chains are complex and its often difficult to identify the precise pinch-points within these logistical processes. Bottlenecks can originate from issues such as:

- Shortage of raw materials to make vital components

- General staff shortages

- Transportation delays due to driver shortages

- Not enough port staff to unload shipping containers

The recent lack of available shipping containers is a good example, with many empty containers in locations where they were placed during the pandemic – places where they are no longer required, but with insufficient labour to move them.

Whilst the supply complexities continue, the demand for goods and raw materials is increasing and potentially outstripping supply of many of those commodities.

The past 3 years have proven to be a major test of resilience for many manufacturing sectors, not least aerospace. Not only did the aviation sector see air-travel reduce by 97% in 2020, but it also saw a 55% drop in orders for commercial aircraft.

The sanctions placed on Russia has also put pressure on the industry’s supply of aerospace grade titanium – critical to aircraft manufacturing for its weight relative to strength and compatibility with new generation carbon-fibre, used in long haul aircraft.

‘Whenever there is a challenge, there is also an opportunity to face it,

to demonstrate and develop our will and determination.’Dalai Lama

The media often uses the ‘headwind’ analogy to describe the situation faced by the aerospace industry during these unsettled times – a ‘perfect storm’ may be a more appropriate metaphor given the scale of uncertainty.

With demand for titanium rebounding and increased demand for critical raw materials from other sectors, the industry must not only source new suppliers but re-evaluate how they manage their superalloy and titanium supplies.

The relative scarcity of these vital materials sets a new challenge for the aerospace sector, which time and time again has shown itself as a dynamic and leading force when it comes to sustainability and innovation.

Given the ongoing geo-political tensions between the West and Russia, it is unrealistic to expect a thaw in relations anytime soon.

The recent state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Moscow, signifies closer collaboration between the two powers that could eventually lead to sanctions imposed on China and yet tighter restrictions on global titanium supply.

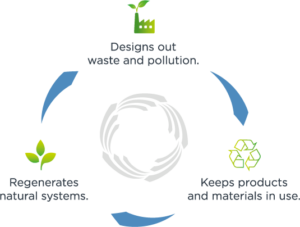

The circular economy

The industry must reduce its dependency on primary critical raw materials through circular use of resources, secondary raw materials, sustainable products, and innovation.

At the heart of this approach is changing the way we think about and manage superalloy and titanium revert in the aerospace industry.

Creating closed superalloy and titanium supply chain loops is the key to strengthening sustainable and responsible domestic sourcing and processing of raw materials through the circular use of resources.

There are multiple benefits to be gained from this approach including:

- Cost savings

- Energy Savings

- Reduced environmental impact

- Increased raw material resilience.

Furthermore, this can be achieved without loss of quality – which often goes unrealized. This is due to negative terminology, often referring to revert material as ‘scrap’ – hence, of lower quality.

Yet, this could not be further from the truth when material is handled and processed by a specialist processor – transforming revert into a secondary raw material.

On a broader scale, a circular economy approach to materials management provides certainty and peace of mind by giving manufacturers more autonomy and control of supplies.

If the aerospace manufacturing supply chain is to fully recover both economically and environmentally, then adopting a circular approach is the best way forward, in a world where traditional sources may no longer be a reliable option.